Left-Right Identities and Political Preferences

The story is famous: since the French National Assembly members were divided into two camps in 1789 (the supporters of the revolution on the left, and the supporters of the status quo on the right), political ideologies came to be classified across the left-right political spectrum.

This formulation had several connotations, namely, “the right” generally referred to positions characterized by system maintenance, conservatism, and order, while “the left” generally referred to system change, progressivism, protest, and socialism (see Jost, Federico, and Napier 2009 for a general overview of the left-right spectrum). Hence, the left/right identification enjoyed the heuristic charm of describing ideas, worldviews, policies, or movements—“the ideology as such.”

This is fine and all, but how much of this distinction really makes sense outside the West? Put a little differently, is non-Western public opinion structured around a left/right identity?

Measuring the Organizing Logics

To answer this, I pulled together the joint European Values Study and World Values Survey, which (between 2017 and 2022) asked more than 150,000 individuals across 90 countries a whole bunch of questions about their political views. Crucially, these surveys included the classic left-right placement item, where respondents placed themselves on a left-right identity scale from 1 to 10.

With that in hand, I could ask: does someone’s place on that spectrum line up with what they actually believe about economic redistribution, the nature of competition, gender, and immigration?

I collected 7 questions from the economic domain and 7 questions from the culture domain.

These questions ask about income inequality, private versus state ownership of business, responsibilities of government, private competition, taxes on the rich, unemployment aid, and state’s role in income distribution for the economic domain. When it comes to the cultural domain, the questions ask about having neighbors from a different race or country, gender inequality, whether it is OK to have same-sex relations, and the distribution of jobs to natives and immigrants.

Within each country (there are 78 at the end), I correlated each of these items with the left-right scale to see the extent to which political preferences line up or align with the left-right identity.

A Weak Alignment

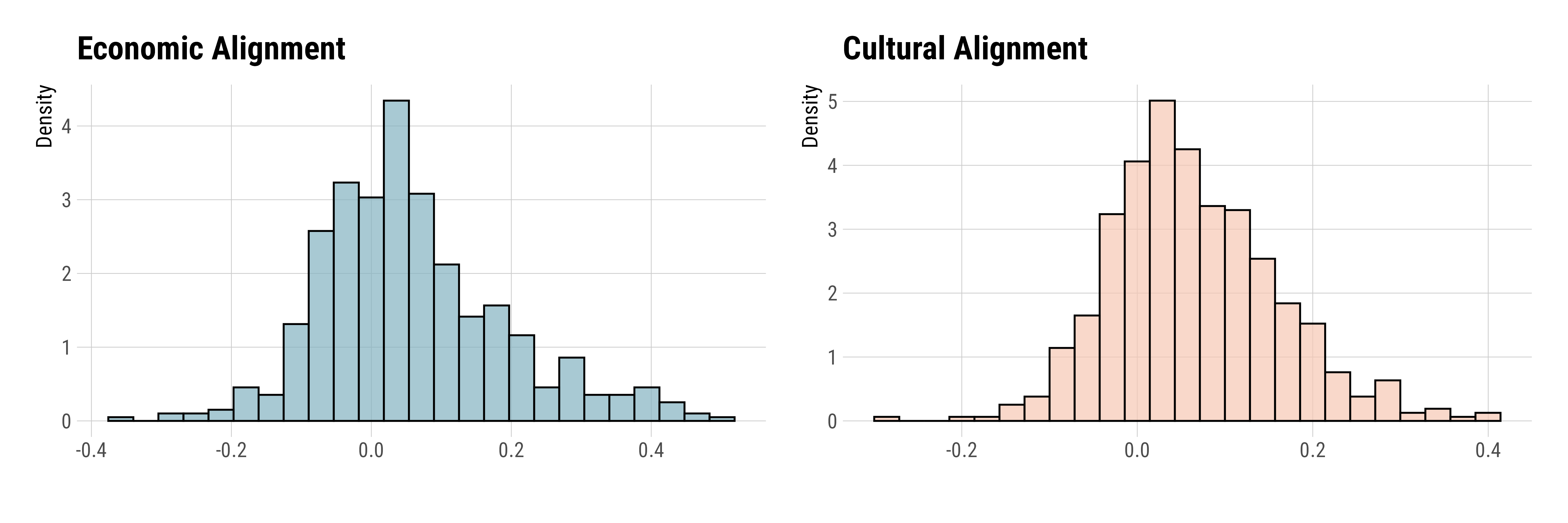

Figure 1 below shows the distribution of these correlations. The observation unit is simply the Spearman correlation coefficient between left-right identity and a political preference or belief at the country level, stratified by the issue domain.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: The Correlations Between Left/Right Position and Political Preferences |

It’s rather messy, but what we see here is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a lot of variation.

While I coded the items in what I thought was a pretty intuitive way (say, folks on the left should be more in favor of redistribution, folks on the right less so), the correlations don’t always line up with that. In many countries, the relationships are actually zero, and in some cases it even flips: you get coefficients as low as –0.4. In short, there’s a ton of variation on this, and the left-right logic does not consistently show up once you look at the patterns globally.

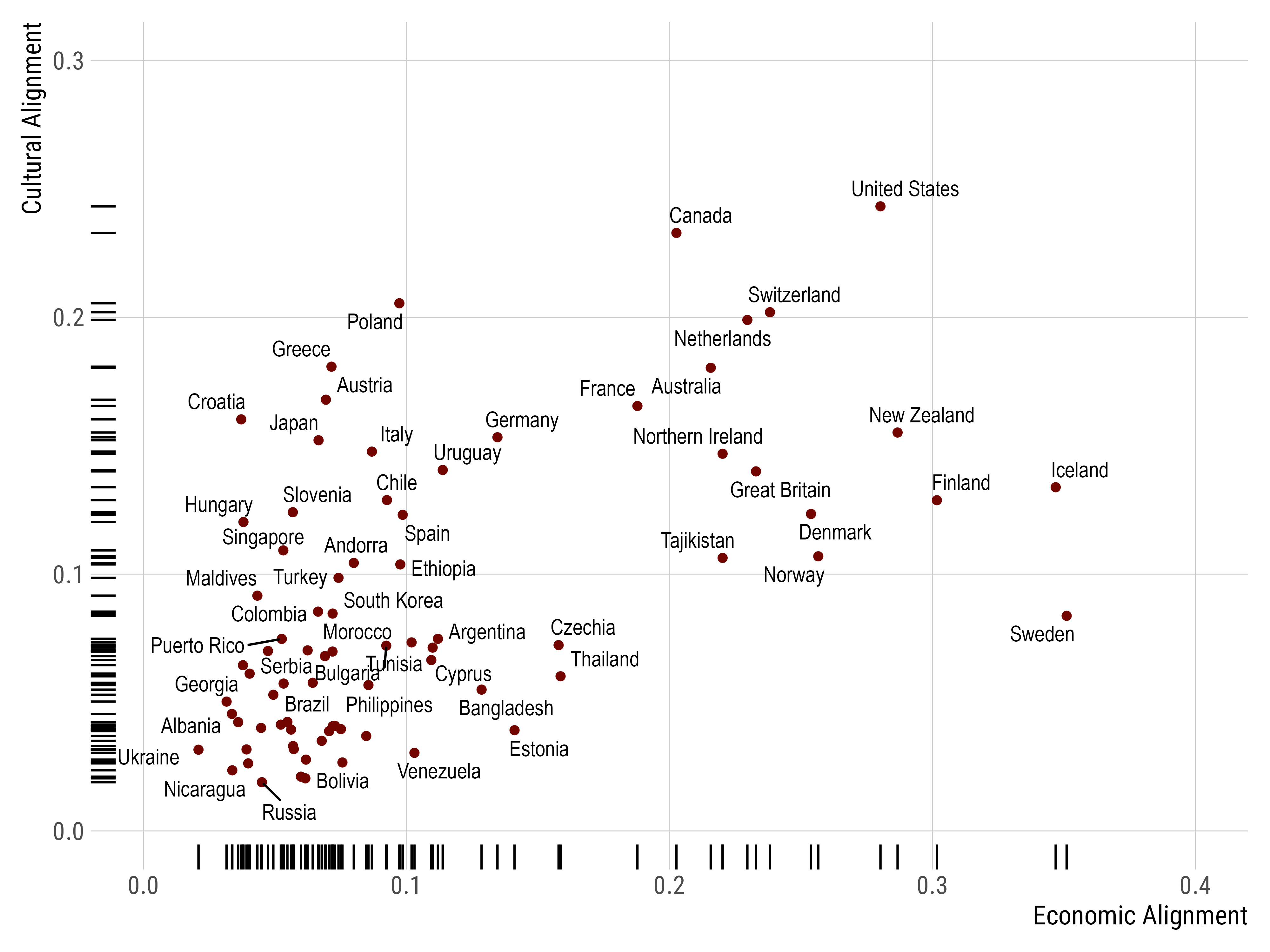

What about if we look at this at the country level? To do so, I built two “alignment” scores1: one for economics and one for culture. Figure 2 presents these scores, with countries labeled.

1 I basically took the average of absolute correlations.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: The Political Alignment Across Countries |

In most countries, the correlation between left-right identity and actual beliefs and preferences was very weak, except a few outliers, all of which are WEIRD countries.2

2 Obviously, the United States is one of the big ones.

The replication files for this exercise are here. Play with it in any way you prefer!

Let me do a little shameless plug as well: I examined the issue of constraint (the extent to which things go together) using this data—looking at the correlational structure across these countries in a larger setup. My answer to the question of why we see so much variation is simple: where political party systems are institutionalized along clear ideological lines, you also find people with much more ideologically structured belief systems. See the article here if you want to read more.